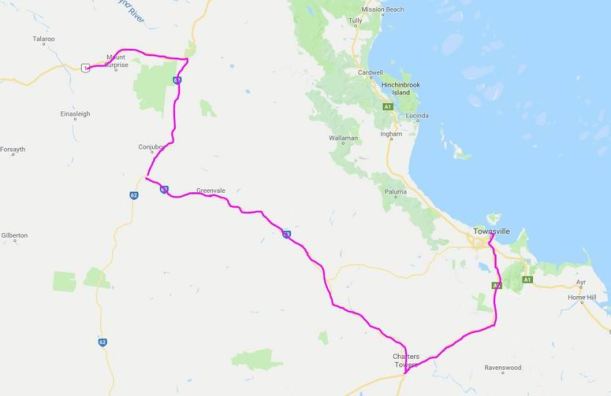

FRIDAY 8 NOVEMBER TO SUNDAY 8 DECEMBER AYR

Back to getting up to the alarm clock! Early – in order to have time for breakfast and to pack the day’s food.

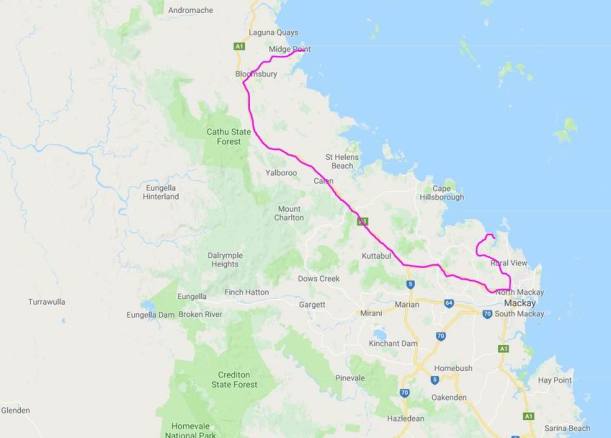

We found that the drive to Giru usually took about half an hour, for the 40 or so kms, but we tended to allow 45 minutes, because we had to negotiate some town traffic in Ayr.

It was a pretty drive, through farmland growing sugar cane and mangoes. One we did not get sick of. Morning traffic was not bad as we usually had to start work at 7.30 or 8am, so were heading through Ayr quite early. It was also mostly quite cool at that time of day.

As our time at Ayr progressed more towards the wet season, there would sometimes be some really dramatic storm cloud build-ups, to see as we drove our beaten path. There were some really heavy rain downpours too. Some nights we worked until late, so were driving back in the dark.

We took our packed lunches and drinks for the day – there were no shops anywhere near the packing shed, and our breaks were not long. I soon got into the habit of packing something we could eat for tea, as well, if it looked even remotely likely that we could be doing a late run of fruit. The little esky chiller, with a couple of cans of cold Coke in, kept the food cool.

Our first day was getting oriented, and doing training.

I was assigned to the packing lines, and John initially to the washing area.

There were numbers of other workers in the shed – variable in number, but generally about 20 or so – often not enough! There were desappers, sorters, packers, forklift drivers, people who put labels on the fruit (after packing) and closed boxes, and quality control checkers. Outside, there were the pickers.

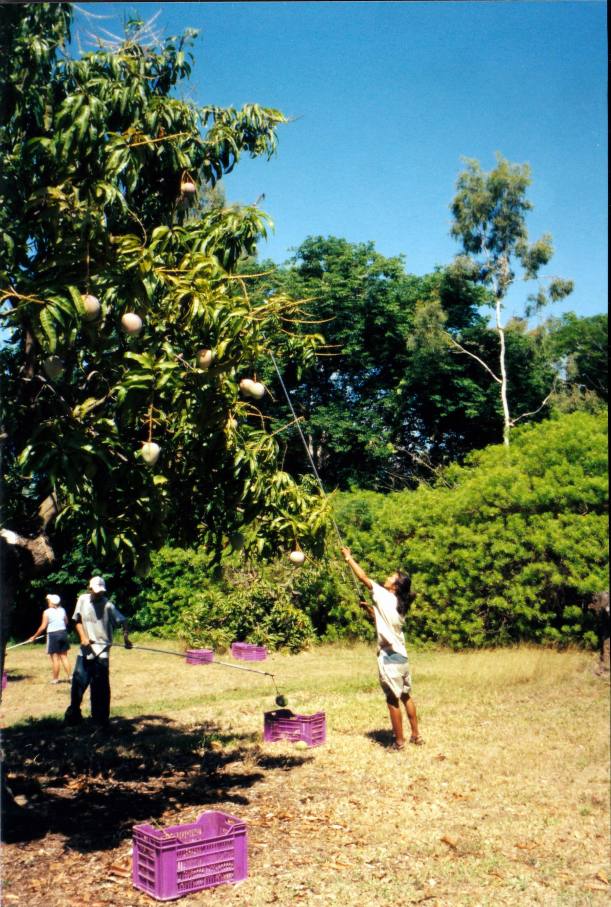

Picking mangoes

The workers ranged from grey nomads like ourselves, who were essentially travellers, to older people (and a few younger) who followed the “harvest trail” around the country – moving from one seasonal fruit/vegetable, to the next in another part of the country. There were some overseas backpackers.

We were told by some of the old hands, who had worked here previous seasons, that the local workers now refused to work in this shed, and some of the harvest trail workers also would not return, because of the two women who managed the shed. They had managed it for a couple of the previous seasons and had gained a reputation. They were a couple and were quite nasty people – and very poor bosses to work for. They were rude and abusive to workers and downright bullies. The few backpackers who started with us did not last long, as they were particular targets and refused to take the treatment meted out to them.

A few of the harvest trail types had rigs parked out behind the packing shed. I think there were some primitive facilities out there for them. A few were at Ayr, like us. The backpackers were in hostels in Ayr.

Picking the mangoes was a male province. The mangoes were picked from the ground level, using long poles. In theory they were still somewhat green and were picked in the afternoons. They sat overnight, in crates, outside, with stems still attached. This allowed the sap to settle in the stems and stem attachment area.

The next day, they went to the washing area in the shed. Here, they were de-sapped, by removing the stems, whilst holding the fruit upside down. This was sone under running water, partly because the sap was very caustic to people’s skin, and partly because any sap contacting the mango skin would leave a sap burn that would later cause the fruit to rot in its box, and potentially ruin a whole box of fruit. We quickly learned that the great enemy was sap burn!

Desapping mangoes

Desappers wore long, heavy gloves, and skin protectors, and waterproof aprons. It was a messy job. Most of the desappers were female backpackers.

Occasionally a snake of some sort would find its way into a mango crate during the night, and then cause a major stir in the desapping area when it surfaced next day.

From the washing area, the fruit moved on conveyor belt rollers to the sorting tables in the adjacent section of shed. Rotating rollers moved the fruit along – the speed of movement could be varied by the bosses, but it was always fairly fast.

Sorters stood in a line each side of the sorting “tables” – the rollers – and picked out any fruit they saw that was sap burnt, had marked skin, was undersized – or was ripe. Packed mangoes had to be still green – after storage, they would be gassed to ripen them at the required time.

The sorters closest to where the fruit arrived from the washing area, were the busiest, those at the far end often had few problems left to find. They rotated their order regularly. The sorters often looked quite comical, scrabbling away really quickly, grabbing fruit with both hands as it passed by them, and dropping their reject finds onto a small separate conveyor belt in front of them, from where it would go into the bins to be sold for juicing.

John working on the sorting table

Some of the ripe ones were kept aside so staff could take them. We ate a lot of mango in those weeks!

A surprisingly small proportion of the desapped mangoes actually made it from the sorting tables to the packing area. The bosses would periodically check over a selection of the rejected fruit, to make sure that the sorters were not discarding good mangoes.

The sorters were a mix of men and women.

Runs of mangoes were done by type. This shed worked mostly with Kensington Pride mangoes – or KP’s. Later in our time there, we had some runs of R2E2’s – a much larger fruit that was destined for the Japanese markets, for Xmas, where they were expected to fetch over $20 per mango! Extra care was taken with the R2E2 runs.

From the sorting area, the fruit was conveyed along a line that automatically sorted by size. Size was designated by the number of mangoes packed to a standard box. e.g. 20’s fitted 20 in a box; 22’s fitted 22. KP’s ranged mostly from a very few 14’s, through to 24’s – but mostly 18, 20 and 22.

A packer would work at a packing station where fruit of all one size was delivered via a roller belt, at about eye height, into a large bin beside the packer. They would pack on a small bench area then push each filled box onto a lower roller belt for delivery to the end area of the shed, for labelling and sealing.

There were different packing patterns for each size, to fit the right number of mangoes into the box in a way that would protect the fruit during transit. I learned the main patterns on the first day – and there were diagrams stuck up at each packing station to jog the memory. The mangoes were always lined up in their box pointing in the same direction and the same way up. so the appearance was a very uniform one.

Packing. Note the uniform layout of fruit packed in the box

A packer had to work fairly quickly – almost frantically at times when there was a lot of fruit and the bosses speeded up all the processes. If a bin overflowed the fruit could not be packed, but had to go for juicing, so there could be considerable pressure not to let this happen. Packers had no control over the rate of fruit delivery – if the speed at which fruit was delivered from the wash to the sorting tables was hastened, or if two or three sorting tables were operating, things got busy at our end! The pressure was not helped by the bullying tactics of the nasty bosses.

Packers also had to be on constant watch for any faulty fruit that had been missed by the sorters – usually with sap burn – so one had to pick a mango out of the bin, turn it over and inspect it, as part of the packing process.

Sometimes, if some of the sizes did not have many coming through, those of us packing would have to keep watch on the bins on either side of us, and move to packing at any station where the bin was getting close to overflowing.

A packer would take a box from a conveyor belt above head height – assembled elsewhere – and put the box on the bench in front of you. You would pack it, then slide the box forward onto the lower rollers, and it would trundle away.

The packing line

The whole process was really quite interesting, and had it not been for those two bosses, I would really have enjoyed the job. It could be very tiring, some days, although we got regulation breaks – mid-morning and afternoon, and lunch – which helped greatly. The shed was not too hot, mostly, though one often worked up a good sweat.

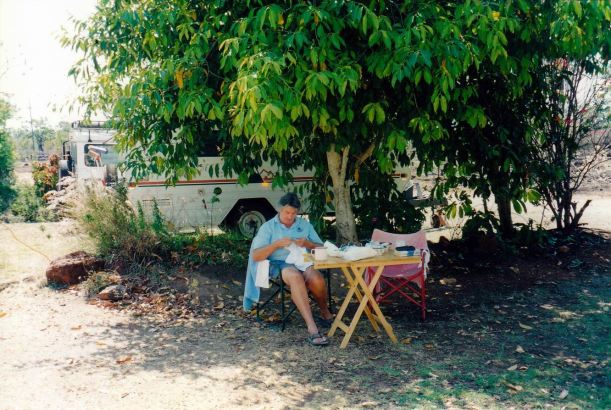

Lunch time in the packing shed

John found the rubber gloves of the desapping lines really irritated his skin, so after a few days he moved to the sorting tables, which he enjoyed. I sometimes got drafted to sorting, too. John did a little bit of packing, but the boss woman in that part of the shed did not want men workers in her section – she could bully females better!

The end section where labelling sealing etc were done, and the boxes forklifted off into the cold storage room, was staffed predominantly by men – the partners of some of the packers.

There was a Sungold packing shed across the road from ours. They worked set hours – 8am till 5pm – and the workers there received a set wage. Our shed – which handled fruit from several different plantations, including that trucked down from Townsville – worked hours according to fruit supply. That was why we were paid by the hour. There were a few days when we worked from 7am till 11 at night! That was great for the pay packet, but exhausting.

Mango orchard at Giru

We worked also to a rule that said if there was a breakdown or a problem in the shed, that was under the company’s control, then we got paid for any time spent waiting around for the place to become operational again. If there was an external problem, out of company control, like a power outage, we did not get paid for waiting around time. That only happened once, when the power went down, and after a little while we were sent home early, so that was fair.

As well as our pay, we received the mandated superannuation. We were happy with our wages – some weeks, we banked over $2000 between us.

The shed operated 7 days a week, when the fruit was ready, so we rarely had days off. The biggest problem this caused was that we soon found it hard to get provisions. We were away in the mornings before the shops opened, and home after they had closed. We just had to stock up on the rare occasions that we finished early – and hope. I managed to always have some mangoes – the ripe rejects from work – to eat at “home”, if all else failed. We always had these for breakfast. Did not get sick of them, at all.

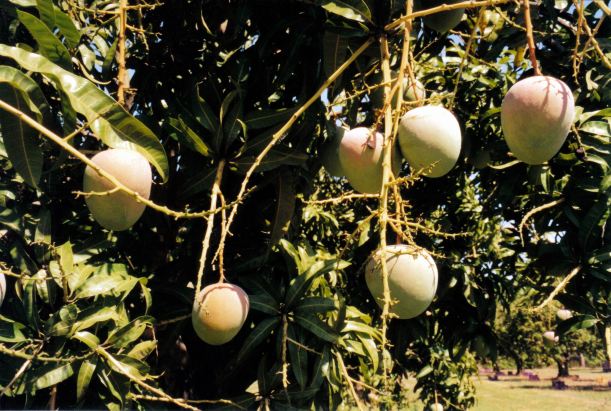

R2E2 mangoes – freebies

Doing the washing was another issue – but the park laundry had really liberal hours, so running a machine at 10pm was permitted , even if it wasn’t desirable from my viewpoint.

So we cherished the rare days off!

I found the other workers in the sorting and packing areas to be very pleasant, and interesting. After the mangoes were finished, some would head to Victoria for the Goulburn Valley fruit harvest, or to Mildura for the citrus and grape harvests. Then they would return to Qld for the beans and tomatoes of the Bowen area. Some had started with the earlier mango season around Cairns and followed them south. We gained interesting insights into that way of life, which seemed to be a healthy and comfortable one for those on the harvest trail. They had holiday periods in between the various harvests, travelling slowly or going a long way round to see different places.

Mango work had its hazards. While we were there, a backpacker got a spray of mango sap in her eyes and had to go to hospital. Some people developed “mango rash” – a sensitivity to the fruit – and had to stop working with them. Towards the end of my time there. I had some small, itchy, rash areas on my arms, but thought it was just heat rash. We sweated quite a lot in the sheds.

John walked into the tow hitch on the back of Truck and took a chunk out of his shin. This became infected after a couple of days, and he ended up having to go to the outpatients department at Ayr Hospital for treatment. A fortuitous early finish one afternoon was very timely, here. Once the wound was dressed, and he had some anti-biotics, he kept going to work.

One afternoon, when we were told there would be a late run of fruit, one of the backpacker girls asked nastier boss if she could finish by 9pm, because there was a farewell party at the hostel for friends who were leaving, and for her birthday. We actually finished the packing a bit before 9, but then nasty boss deliberately assigned that girl to the clean up team – washing off the rollers, tidying up and the like, so she didn’t finish until after 10pm. It was after this little exercise of power that the backpackers all stopped working at the shed.

Over the weeks, the workers – including us – had become increasingly fed up with the antics of this woman. Other people found it too much, and left, so at times we were really short on the sorting and packing areas.

Mangoes ready for picking

The harvest was supposed to continue well into December and probably into the New Year. We had initially intended to go the full distance, into January, but along with many of the older staff, began talking about pulling out too. I couldn’t understand why the main company management let these two women run the shed, given the labour problems they created.

John was actually fairly keen to be home for Xmas.

The last straw for us came on Saturday 7th December. We’d had storms and a power outage a couple of days before, that stopped a whole day’s work, so there was a backlog of fruit.

Another nomad couple had been put on and the lady was learning the packing, and was doing quite well, I thought. It did take a few days to get properly into the routine of the different packing layouts, to the point of doing them evenly and quickly. The bosses decided to run a third sorting table, thus tripling the usual quantity of fruit coming the way of the by now very under-staffed packing area.

We were packing like crazy, and were told off because some fruit bins overflowed – there were just not enough workers to keep up with the volume of fruit arriving. The new lady, with bins about to overflow on either side of her, called out that we needed help, over here. The response of boss lady was “Well, you bitches will just have to f****** pack faster!” Really helpful, that. Then there was the tirade, in the same vein, once the bins did overflow.

That was it, for me. At the later than usual lunch break I told John we were out of the place. Some of the others left with us.

So we drove the commute back to Ayr for the last time. As it happened, the sky was suitably stormy.

We used our last day in Ayr – Sunday – to get the van tidied and gear packed away, do the washing, fuel up Truck, say farewell to friends we had made in the park. Over our time at Ayr, given our lengthy commute to Giru each day, we’d bought diesel several times at the Woolworth’s servo at prices from 80-82cpl.

Farewell drinks at the caravan park

In the laundry, I dropped my glasses on the tiled floor and broke them. New glasses would be on the agenda, when we got home again.

No fixing these!

Over our time in the park, our weekly metered power bill had varied between $5.50 and $12.85, depending on the hours we worked and were not home. We had not been running the somewhat noisy air con on the hot nights, relying instead on the box fan set up on the table at the far end of the van and blowing air our way. With this and the good cross ventilation from the windows at each end of the bed, we were fine.