The school:

On paper, there was an enrolment of 360 students, in Years 1-10. There were 28 teachers, plus about 16 aboriginal teachers’ aides- only a few of whom turned up on any given day, and not in any predictable manner. These were all women. An aide would sit in a classroom – chosen by her – and watch proceedings, but did not actually do anything else. So they were more observers than any actual help to the teacher.

One of the several major problems for the school lay in the clan group/family warfare of the community. Certain groups of students would not attend school when other groups were there. Ditto the teachers’ aides. Classroom and playground dynamics remained a mystery to us.

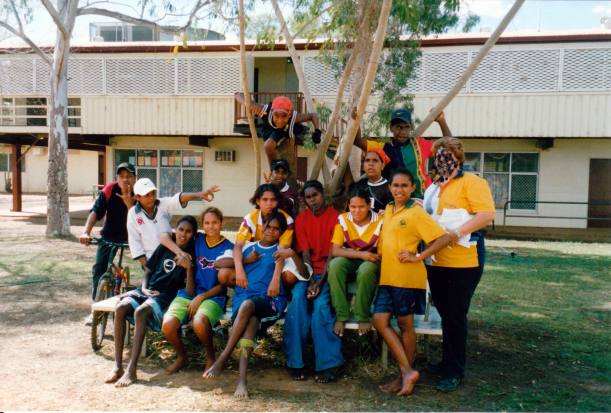

The enrolment figures were derived from the start of the school year – in the Wet season – when Doomadgee was cut off from anywhere else. So, going to school was something to do. By August, there were about 60 students who attended fairly regularly. Others drifted in and out, from day to day, depending on what else was going on in the region, and their mood, and whether there was something like sport happening.

It was obviously very hard to run classes systematically, when no-one knew until 8.45am, whether there would be 0 or 50 kids in a class! Some primary classes had been formed from fairly regular attendees, and teaching here could be a bit more predictable and able to be planned. An example was a composite class of Years 2,3 and 4 of regular attendees. Other classes were designated for catching the day’s unpredictable arrivals. An example was a Year 2,3,4 class of irregulars – on any given day there could be no-one, or 50, in this group! So teaching bodies had to quite often be shuffled around at the start of each day.

For some of the irregular attendees, it might be their first day back at school for a week, or a month, or a term! They may decide to leave again, part way through the day, and not be seen again, maybe ever. Trying to deliver any meaningful or effective schooling to this group was well nigh impossible.

There was one secondary girls’ class, covering, nominally, Years 8-10. The 14 girls in this group attended most days. I use the term “nominally” because the achievement levels of these Year 8-10 girls ranged from about Year 3 to Year 7, as we would understand it. There was a smaller, equivalent boys’ class – usually about 7 of them. As well, there was a class of “feral” secondary age boys – fairly regular attendees but basically un-educable, due to their lack of any discipline or self control, and/or any accumulated learning to date. The school was obliged to do something with them. Two young male teachers were usually assigned to this group, together – to take them to practical, physical and outdoor activities, totally removed from the rest of the school. They were, essentially, uncontrollable and at times a danger to themselves and each other, not to mention the teachers!

The Principal – who had been responsible for persuading John to come up here – seemed to spend a lot of time away from the place. He was on various committees, union and working groups that met in places other than Doomadgee – Mt Isa, Cairns etc. We actually wondered if he was somewhat wary of being in the place, and possibly inadvertently doing something that would spark another riot. He usually drove to wherever his meetings were, rather than utilizing the daily Mt Isa-Doomadgee-Cairns plane, so the time taken driving added to the time he was required to be away.

The Qld Education Department offered inducements for staff to go to schools like Doomadgee, Mornington Island, places on Cape York. For someone who took on the Principal role – and he was quite young for this – two years running Doomadgee would guarantee him Principalship of a better school. The majority of the teachers were in their first or second year of teaching, and for most of them, this was the only way they could get accepted into the Department. If they lasted two years, they became permanent. So, from their cohorts of recent graduates, they had not been chosen for other schools. So, the majority of the staff were enduring their two years. But there were some who were trying their hardest to make a difference.

The Deputy Principal was the lady who lived in the other half of our duplex. She was middle aged and an experienced teacher. We found her really genuine in her efforts to improve the quality of educational delivery in the place, if somewhat idealistic. I guess one had to have hope and idealism to survive in such a school. The teenage girls seemed to respect her, as much as they did anyone. Under her guidance, the focus of the school was on literacy and trying to improve same.

The Senior Master had spent time on Mornington Island, before coming here, so he was experienced in difficult indigenous schools. He was a loud and bulky man and these qualities seemed to have some disciplinary effect on some of the boys. He was responsible for the daily organization of the school. When we arrived, it was weeks into Term 3, and there was still no operating timetable!

There was a part time, experienced, lady designated as the literacy/special education director. She seemed to see John as a threat, from the outset, and was not at all helpful. Another experienced lady came in part-time from somewhere else, a few times, as the Psychology advisor.

A woman who had been teaching for a few years was the secondary girls’ teacher. She took them for all core work: literacy, numeracy, social studies and the like. In the time we were there, she never worked a full five days straight – always taking off either a Monday or Friday, each week. She was quite open about this; there seemed little the admin could do about it. She consorted with some of the locals and went off on three day camping weekends with them. The leading women in the community disliked her intensely – apparently she had offended local custom by giving the girls some rather frank sex education classes. But the girls obeyed her – albeit in a fairly surly way. I didn’t see much evidence of respect for her, though. I will refer to her as “S” – for secondary.

S had also clashed, earlier in the year, with the teenage daughter of one of the prominent community families. Daughter had gone off to board at Shalom College, in Townsville, at the start of the year – nominally at Year 10 level. However, Shalom posted her back home, sometime in Term 2. The girl was semi-feral and very disruptive – possibly because she was, under it all, quite intelligent. She and teacher had then clashed, on a school trip to Cairns, and the girl had brandished a pitchfork at the teacher. Student had had a period of exclusion from school but after that ended, refused to attend. S refused to have her back, so it was a stand-off. By my standards and expectations, she’d have been permanently expelled and not allowed back at all.

Unfortunately, when S was on one of her weekly days off, somehow the word would get round that I was taking the girls’ group, and the disruptive girl would show up. I wished she wouldn’t! She was insolent, totally full of herself because of her family’s prominence, and even after the Shalom experience, showed no indication of being motivated to improve her low standards, despite said intelligence. As far as I could tell, she came to school to make the point that she could – and to swan around making a pest of herself in class. Fortunately, the rest of the secondary girls were quite pleasant, and willing to try in class.

The experience of this girl was typical of what happened to those students who were sent away to other schools. They just didn’t last out there. There was too much of a gap, in learning terms, between where they should have been, and where they were. The same often applied to behaviour too, especially in a boarding school context. Very sad.

S’s teaching methodology was to get the girls to work on photocopied handout sheets – taken from various sources, not made up herself to suit the kids. From the piles of these in the classroom, it was clear she didn’t bother to check or correct the sheets they completed. There was very little actual instruction on how to do anything. I formed the impression that this sort of handout work was the main way of trying to keep the kids busy, in many of the classrooms.

The girls did enjoy the time, each morning, when S read to them from a novel. A book was quite a novelty.

When we started, there was a local lad on the teaching staff, who had qualified to teach in some sort of special program for aboriginals – he was a real success story. Doomadgee was his first teaching post, and he turned out to have made a mistake in coming home for it. Not long into our stay, he resigned – because the living conditions in his family’s home, and the lifestyle the family expected him to participate in, was not compatible with working standard days. Sleepless nights, inability to do any work at home, or keep any school materials safe there, contributed. It was very sad, but symptomatic of the barriers facing those who have more ability and drive than the average community member.

An American drama/music teacher who was there when we arrived, disappeared a few weeks later. He disgraced himself on a weekend visit to Escott Lodge, with some extremely drunken behaviour, and was banished.

One of the primary teachers was a bit older than the average – around thirty. She worked in a Grade 2-3 class – not the best of these groups – but seemed to be constantly gathering in students outside that range, that the other teachers found hard to work with. I couldn’t tell whether this was to try to help them survive, or to demonstrate her own superiority. The result was that her very large class contained some challenging behaviours. Later in August, she – supposedly – left for parts south, to see a sick sister. It was fairly obviously an excuse to get out of a situation in which she was not coping. We knew she would not return.

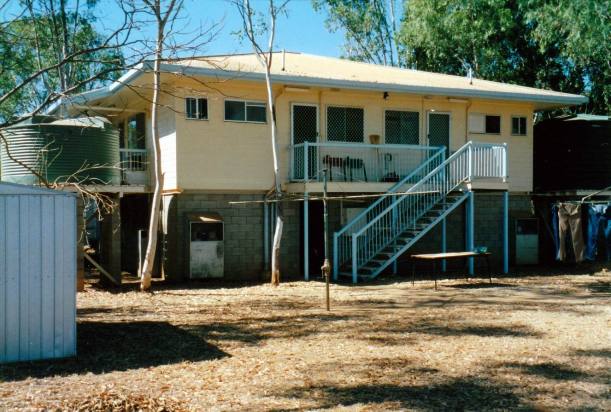

Through much of Semester 1, there had been a Home Economics teacher, but she had fled in Term 2, and not been replaced. Our house had been hers.

After a few weeks, I decided that, of the entire staff, there was only one I would definitely have in a school I was leading, with another two possibles. Forget the rest, in terms of being, or becoming, talented and enthusiastic teachers.

The school had a canteen, run by local mothers. School staff input was not welcomed here. It would not have met any canteen standards in a normal school, in regard to hygiene, food preparation, adherence to use-by dates. During the mornings when lunches were being prepared, toddlers in filthy nappies and with streaming noses, played on the floor or were sat on the benches to watch. A number of dogs wandered in and out. The canteen did not open regularly, but three times a week provided “free” (government funded) lunches for the students. These were usually white bread sandwiches, dim sims, and the like.

The brown kites – of which there were large numbers around the community, due to its volumes of rubbish lying about – were very well fed on free lunch days. Kids would take a bite or two from a sandwich, decide they didn’t like the filling, and chuck it away.

One local lady ran a breakfast club, of sorts, to give some children breakfast before school. It operated very intermittently and unpredictably, and only fed a few kids. I suspected there was some government funding for this, and that the few who were thus fed, came from her own extended family.

There was so much money being poured into the school and its associated programs – and so little return for same. So much waste. There was a room full of expensive musical instruments – many broken. A program would be proposed, be equipped and begin, then the teacher would be gone, and that was it.

There was funding for sporting excursions – which meant going to places like Cairns. At least, the kids enjoyed those and benefitted from glimpses of the world outside the NW Gulf country.

A (funded, again) visiting chef/cook came for two days while I was there, and ran a program with the better behaved secondary girls and boys. Supposedly, it was to show them what work in the food industry was like. However, she did most of the work, assigning the students to basic tasks they could manage, without them really knowing where what they were doing fitted into an overall plan. The students could not really relate to the processes that resulted in the array of food served to their parents and some community elders, for lunch on the second day. As I had already found, their kitchen skills were rudimentary, at best.

There was a small house-like building, off to one side from the school, that was used for accommodation for outside advisors, and similar visitors to the community, who needed to stay overnight. There was no other guest or commercial accommodation in Doomadgee. Visitors rarely stayed in the community; some went to great lengths to avoid doing so! The preferred option was to stay in Burketown and drive the 90 kms or so, of rough road, each way, even doing so for days in a row.

Qld was introducing the Prep year of schooling in 2003, and there was talk in the school of housing the Preps in that building.

The Technology room, and the Home Economics room, each had an array of school shoes, of varying sizes. The students had to wear shoes in these classes, to adhere to safety standards – mostly they were barefoot the rest of the time. This ensured a degree of punctuality to these classes, as the later comers had to take what shoes were left, regardless of fit.

There was a room equipped with computers – enough for maybe 25 students at a time. This was able to be linked, via Skype, to the outside world. The best teacher – of the best attending kids – had her students doing a regular hook up with those from a southern school.

There did not seem to be any shortage of sports or PE gear. There was a hard surfaced playing area – quite sizeable – that was roofed, and with basketball rings. This area was used for school assemblies too, with the students sitting on the hard surface.

The school had a swimming pool – not in use while we were there, because it was the “cold” time of the year. It also had its own LWB Coaster bus.

In the admin area, there was a well-locked room that was the supplies store, where teaching requisites were kept. This was a school where students were issued with basic needed materials – to be kept in the classrooms at school and not taken home.

There could be no homework given – the majority of students did not have necessary requirements (like writing implements) at home, nor an environment conducive to same. Anything sent home would be lost, damaged. There could obviously be no such thing as a home reading program. Students at all levels wrote with lead pencils, kept in a container in the classroom. Sharpening these to a real point, and using them to stab others, was something we had to watch out for.

Some classrooms had old, tatty, carpet on the floor, complete with a quota of fleas, in some rooms.

All the school windows had heavy duty crimsafe type screens. The secondary girls’ classroom had all its windows heavily draped with blackout curtains. Once the girls were inside for the session, the door to the outside was locked and covered with its black curtain. This was because males from the community would otherwise be hanging about outside, and making pests of themselves, to the extent that some of the girls would not feel safe – teachers too!

There were a couple of occasions, in the uncurtained Home Eco room, where small packs of roving males did peer in the windows and make obscene comments; the door was very securely locked, though, and this room was in a more central part of the school, where they were less likely to venture – compared to the girls’ classroom which was at the edge of the building cluster.

Despite the security mesh or bars on the school windows, there was regular breaking of glass by stones thrown after hours or at weekends. The resulting broken glass lying around was of concern, given that many of the students went around barefoot.

Some 80% of the students had some degree of hearing loss, as is the norm in such communities. All the classrooms were equipped with the Sound Field system, where the teachers wore a box that amplified their voice in a way that allowed all students to hear more clearly what was being said. This in itself was a considerable capital investment.

The childrens’ hearing loss was mostly the result of untreated ear infections when younger. Or poorly treated ones – the chances of a child in the community actually completing a course of prescribed antibiotics were very low. To help counteract the issue of ear and sinus infections, first thing every morning, each primary class was taken outside, by their teacher, complete with large box of tissues, and bin. The students sat for ten minutes, blowing their noses, supervised by the teacher. For some reason, nose blowing was not the norm for younger community children – they just ran, dripped, or got blocked! This was a less than charming way to start the day!

Too many of the students were malnourished and hungry. Scabies was endemic, we were told. As were head lice. We were told by the Senior Master that he put undiluted hair conditioner liberally on his hair, each morning, and did not rinse it off, and this seemed to keep nits at bay. It did nothing for his looks, though. Within days of our arrival, I phoned K and P and asked them to buy and mail up the most effective head lice treatment they could find. There was nothing like this available in the store.

Kids came to school tired, because they roamed the streets freely until all hours, or were on the fringes of loud, all-night gatherings of adults. Even those families who tried to run what we would see as “proper” households, were grossly overcrowded, with 10-20 people per house, and disturbed by the noise from neighbours.

Things that we take for granted in our lives were not present here. Like having a clock, or watch. The school siren was set to be able to be heard over most of the community, as a signal that it is time to come to school. So it was sounded a couple of times after 8am each morning.

A lot of the students were fascinated by the watches that the teachers wore. In that same vein, being allowed to write for a short time with a biro was a great reward.

Children often did not know how old they were, nor when their birthday was. Some of the teachers, who had such data for some, made birthday cakes – often the only indication the child had that it was their birthday.

We take print around us for granted. Not so, here. The school had a library, but these were the only books in the community. There were no newspapers or magazines sold in the store, nor written information around the place. In a culture that is oral based, teachers had to try to change childrens’ mindsets to even think of print as a source of information or entertainment. Though maybe the coming age of computers would kind of jump that step?

School started at 9am and ended at 2.45pm. After roll call and nose blowing, the whole school completed a two hour literacy session. This was the key focus of the school. Then there was a 30 minute “little lunch” break. Then followed 40 minutes of numeracy across the entire school. I felt there should perhaps be less of an imbalance in the times devoted to each of these. After this, the secondary students went into 80 minutes of TAFE programs, three days a week. The TAFE programs on offer were wood/technology related, hospitality or (for a selected very few) computing. The other two days, in this time slot, they did art, woodwork, home economics, mothercraft, computing and the like. “Big lunch” – 30 minutes – went from 1.30pm until 2pm. Numbers of the students did not reappear after this, so the 45 minute afternoon session was for odds and ends – like PE and sport – which had some chance of making them reappear.